It Takes A Tough Man To Choose A Good Advertising Agency

If you lived on the East Coast of the United States and are over 40, you probably know who Frank Perdue was. But for those of you who didn’t and aren’t, Frank was a Maryland farmer/entrepreneur who transformed a father-and-son egg business into a multi-billion dollar international poultry company with more than 20,000 associates and sales in 114 different countries.

What relevance does this achievement have today?

The way he did it is an object lesson for aspiring entrepreneurs. Success didn’t just drop in Frank’s lap; take a look at the time, energy, and resources he was willing to put into just one part of his success, choosing an advertising agency.

In the late 1960s, when chicken was viewed as a commodity, Frank calculated that there was a lot more difference in the quality of chickens than there was between brands of soap or beer. If you could advertise these products, he reasoned, why not advertise his chicken?

Frank decided to do what no chicken farmer had done before. He took a ten weeks absence from running his company, went to New York and began a total immersion, full-time study of the theory and practice of advertising.

It was a big jump for this chicken farmer. There are people in New York today who remember him back then as being so “countrified,” that it was “as if he were wearing high-button shoes and a straw hat.”

One of his first steps was joining the Association of National Advertisers, so he could access their library. In addition to reading books and papers on advertising, he talked with the sales managers of every newspaper, radio and television station in the New York area. He also created a grid of food stores that might purchase Perdue chicken. He then talked with hundreds of these potential buyers about what they wanted in chicken.

When it came to selecting an ad agency, he interviewed sixty-six agencies, and from those, narrowed the selection to six. “The finalists had billings of $19 million, $15 million, and $12 million,” Frank said. “I didn’t go to any of the big ones because I figured I wouldn’t be important to them.”

Then he began systematically calling the clients of the six finalists to find out what kind of experiences the clients had had with the agencies. In the middle of this process, he got an angry phone call. “Why are you calling my clients?” demanded the president of one of the agencies, his voice bristling with irritation.

“Because,” Frank answered coolly, “I can’t tell by looking in your eyes whether you are a priest or a crook.” With a certain relish, Frank continued his phone calls to the rest of the man’s clients.

Even forty years later, Ed McCabe, the copy writer who eventually made Frank famous, still remembers exactly how many agencies Frank interviewed and how many finalists there were. “I know this for certain,” McCabe said in a recent e-mail, “because we all spoke to and commiserated with one another on a regular basis about the hoops Frank was putting us through.”

As told in Esquire Magazine, McCabe said, “You know, Frank, I’m not even sure I want your account any more because you’re such a pain in the ass.” Unperturbed, Frank agreed with McCabe’s judgment and went right on asking more questions.

Barbara Hunter, a friend from Hunter, MacKenzie, Cooper, Inc., public relations, was one of his sounding boards at the time. She remembers the progress of the search, and looking back on it, says, “I’ve never ever seen anyone so thorough. The amazing thing is he did all the research himself, rather than delegating it to someone.”

On April 2, 1971, he made up his mind: it would be Scali, McCabe, Sloves. An agency that was in business five years with total billings of $12 million. Marvin Sloves, the agency’s president wrote to Frank, “If you spend as much time inspecting your chickens as you have our agency, you’ve got to have the best chickens in the world.”

The initial problem copywriter McCabe faced was that with chickens, whatever selling point the copywriters came up with, a competitor could quickly copy it in their advertisements.

McCabe remembers, “Nobody had ever advertised a brand-name chicken before, and just looking at Perdue and listening to him was a new experience too. He looked a little like a chicken himself, and he sounded a little like one. He squawked a lot. About four or five weeks into the assignment it just clicked: Here’s the answer.” McCabe concluded that Frank Perdue himself should be the spokesman.

Frank could give the campaign a unique identity that couldn’t be copied by a competitor. However, as a basically shy man who hadn’t even appeared in a school play, Frank resisted the idea.

Nevertheless, McCabe was able to convince Frank that having Frank Perdue himself was the best way to solve the imitator problem. The campaign based on “It takes a tough man to make a tender chicken” was born. Or hatched.

The ads paid off. In 1967, yearly sales had been $35 million. By 1972, after a year of “It takes a tough man to make a tender chicken,” sales had leapfrogged to $80 million. The advertising budget for the first year was $200,000.

According to a July 13, 1971, column on advertising that appeared in The New York Times, the campaign was off to a flying start soon after Scali, McCabe and Sloves got the account. “In some New York area shops at least, quotations from Mr. Perdue will become far better known than those of Chairman Mao. Examples: Freeze my chickens? I’d sooner eat beef! My fresh young chicken is cheaper than hamburger. Good for you, bad for me. Everybody’s chickens are approved by the government, but only my chickens are approved by me.”

Conclusion

Having expertise in advertising enabled Frank to transform a commodity into a branded item, and in the process, catapulted his company into the ranks of the top poultry producers in the country. But that’s not the real story.

The real story is that a man who grew up on a chicken farm from in a small town in Maryland figured out the importance of advertising; believed in his ideas enough to act on his conviction; had the mental courage to plunge into a field “and a way of life” that was entirely foreign to him; was willing to do the research himself as opposed to delegating it to others; and once he had made his decision, was willing to put himself in the hands of the professionals.

For the record, Frank admired the power of advertising. However, he was always acutely aware that advertising by itself was not enough for success. He loved to quote Bill Bernbach, that “Nothing will destroy a poor product as quickly as good advertising.”

Search Articles

Latest Articles

Perdue: We’re in the Next War, but Without Bullets

https://www.newsmax.com/world/globaltalk/disinformation-troll-farms/2024/05/03/id/1163399 Publication –newsmax.com

Putin Has Vast Vulnerabilities: The Free Russia Foundation Wants To Reveal Them To The West.

https://www.dailywire.com/news/putin-has-vast-vulnerabilities-the-free-russia-foundation-wants-to-reveal-them-to-the-west Publication – dailywire.com

Visiting Ukraine | Mitzi Perdue & Clare Lopez (TPC #1,472)

Visiting Ukraine | Mitzi Perdue & Clare Lopez (TPC #1,472)Watch The Episode About The Episode Clare Lopez and she served in the CIA for 20 years. Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/4bIuk6mPLtjggUUGi9CRPQ?si=Cvn4e_GITyuGEiKI3CiSug&dl_branch=1

Russia’s Ugly Prisoner Exchanges

https://www.realclearworld.com/articles/2024/04/29/russias_ugly_prisoner_exchanges_1028042.html Publication – realclearworld.com

Subscribe to Updates

About Author

Mitzi Perdue is the widow of the poultry magnate, Frank Perdue. She’s the author of How To Make Your Family Business Last and 52 Tips to Combat Human Trafficking. Contact her at www.MitziPerdue.com

All Articles

Learn How to Turn Adversity Into Opportunity

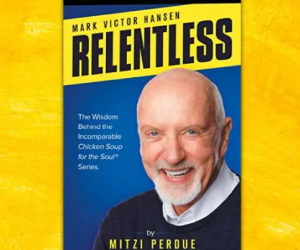

Learn How to Turn Adversity Into Opportunity“Use adversity as a bridge to your destiny.” Those are nice words to live by, especially if it works and your destiny turns out to be fulfilling and rewarding. People probably view Mark Victor Hansen’s destiny as a...

When it Comes to Vendors and Services, Size Matters

When it Comes to Vendors and Services, Size MattersWhen you’re evaluating outside vendors or services for your family office clients, is the size of the company you’re looking at one of your important considerations? It was a crucial screen for my late husband, Frank...

Shifting to a High-Functioning Family

Shifting to a High-Functioning FamilyYou’ve heard of a Tale of Two Cities by Dickens, right? Today’s topic is a Tale of Two Families and the person who can tell the story is Steve Legler, a family business speaker, author, and advisor. The two families he has in mind...

Are You Paying Attention to Both Parts of Succession Planning?

Are You Paying Attention to Both Parts of Succession Planning?There are two major components of family business succession, but all too often family business owners focus on only one. The result is missed opportunities and the potential for family dysfunction. The two...

Your Family’s Greatest Heirloom

Your Family’s Greatest Heirloom“There’s nothing greater you can give your family than this,” says Jamie Yuenger, founder of StoryKeep. “Provide those who come after you with the tools for personal, emotional, and spiritual success.” The way to do this, she believes,...

Want your family business to last ? Five tips for getting there.

Want your family business to last ? Five tips for getting there. View ArticleSearch ArticlesLatest ArticlesSubscribe to UpdatesAbout AuthorMitzi Perdue is the widow of the poultry magnate, Frank Perdue. She’s the author of How To Make Your Family Business Last and 52...